In last

week’s post, I provided some background on force fields – what they are,

what creates them, and how we can sense them.

This is actually at the heart of my research. Specifically, I try to find out what types of

materials are magnetic, and under what conditions. Sounds boring, I know. So my job today is to convince you otherwise.

What if I told you that I built an apparatus that “sees”

force fields? I refer to it as a

microscope, simply because it takes images of very tiny objects. It is not however, a microscope in the

often-used sense of the word: I don’t look through a set of lenses to focus on

the object of interest.

To explain how my “force microscope” works, recall the

refrigerator magnets from last week. You

could only tell that they were magnetic because you had two of them, and they

exerted forces on one another. If you

instead had one unknown chunk of material, you would need a second object – already

known to be magnetic – in order to test if the unknown is also magnetic. This is exactly how my microscope works. I measure the magnetic and electric forces

between the sample I am studying (the unknown) and a small lever (which I know

to be magnetic and/or charged).

The lever is like a really small diving board. Really small.

Imagine a diving board as long as a human hair is wide. That’s just about right.

The lever hovers just above an “unknown” sample. Just as a diving board bends due to the force

of a diver’s weight, this lever will bend when it experiences a force. For example, by placing a tiny magnet on the

end of the lever, I can detect magnetic forces.

Since like poles repel and opposite poles attract, the lever can sense

if the sample is magnetic by deflecting, or bending.

|

| A magnet on the end of the lever causes the lever to bend in response to magnetic forces. This allows me to determine if a sample is magnetic. |

Alternatively, I can put a little bit of electric charge on

the end of this lever. This allows me to

sense electric forces.

Because it’s so tiny, the lever will bend in response to

very small forces. How small? Consider the mass of a feather – about 1 gram. Imagine it

resting on your hand. Not much force certainly,

but still perceptible: you can feel some small amount of pressure on your

fingertips. This tiny lever can detect

forces one trillion times smaller than

that. I’m not using “one trillion”

as a colloquialism here… I mean it quite literally. It’s obviously tough to draw a comparison to

everyday experience here. If I were to

place a single red blood cell on the end of this cantilever, it would cause a huge amount of bending, because even it is

100 times heavier than the smallest force the lever could detect.

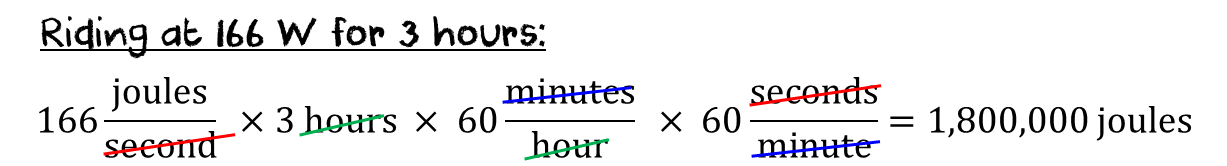

Just to show you how cool this really is, here are a couple

of images I’ve taken with my microscope.

|

The sample that I’m “looking” at here is a computer hard

drive. The cartoon at the right shows

that a hard drive consists of magnetic regions: these are the 0s and 1s of

digital information. You see, inside

your computer’s hard drive is a disc of literally billions of these tiny

magnetic regions. Their precise ordering

(white-white-red-white-red-red-white-red OR 00101101, etc.) is how your songs,

documents, and photos are saved. For

more about how binary code works, visit this video, and be sure

to check out my favorite musical tribute to binary code.

On the left is the image of that hard drive obtained with my

microscope. The colors in the image aren’t

the actual colors of the disc – remember: I’m not looking through a microscope

with lenses. Rather, this “false color

image” is sort of like the weather radar map: the rain clouds aren’t

actually red and green, but rather, the meteorologists use red to denote heavy rain

and green for light rain. I’m doing

something similar here. The color blue

indicates an attractive force that pulls the lever towards the sample (just

like two attracting refrigerator magnets). Dark red is the opposite: a repulsive force pushing the lever away. And just to provide a sense of scale, about 12

of these images could fit across the width of a human hair.

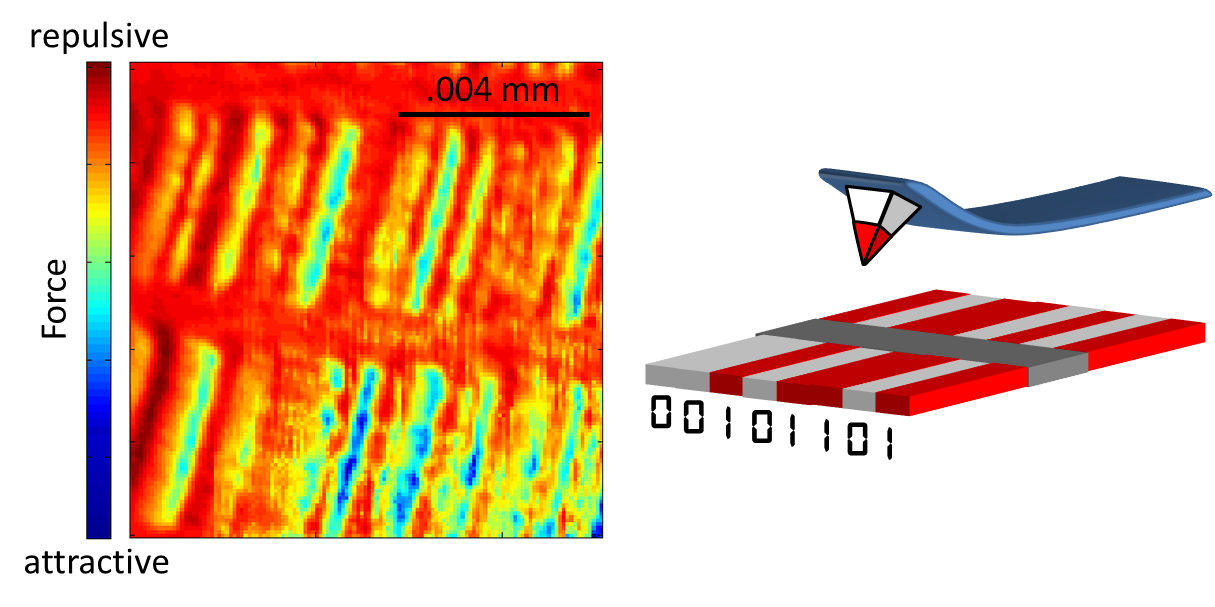

Next, I show an image of a tiny electronic circuit. The processors, or “brains”, of the

computers, cell phones, and tablets that we use today have billions of circuits

comprising them. To fit that many

circuits into a device that fits in the palm of your hand, those circuits must

be very small. The circuit we're looking

at here is actually monstrous by those standards. It measures about 10 micrometers

across (one tenth the width of the human hair seen above). In this space, you could fit 500 of the individual circuits

used in a state-of-the-art Intel processor!

Remember in “Everything is a voltage” that charges are pushed around by voltages. I like to think of voltages as hills and valleys that the charges roll through. Well, that’s all that I’m doing with this simple circuit. You can see in the bottom cartoon that I’ve hooked up a battery to the two arms of the micro-circuit. The positive terminal of the battery “carries” positive charges to the top of the voltage “hill” and piles them up on the left arm of the micro-circuit (marked (+) because it has an excess of positive charge). The charges then “fall down” to the lower voltage at the right arm of the circuit (connected to the negative terminal of the battery). This is simply electrical current traveling from left-to-right.

The force image shows that the pile up of positive charges on the

left arm causes a strong attractive force on the lever (which has a bit of

negative charge on it).

This is the top of the voltage “hill”.

Moving from left to right you can see that the measured force becomes

less attractive, and finally, at the right arm, we arrive at the bottom of the

voltage hill where there is no force between the lever and the sample. You

might have expected a repulsive force here (since the lever has a negative charge, and the right arm is connected to the (-) terminal of the battery). However, I've also connected the (-)

terminal of the battery to “ground” – that is, no charge. Without any

charge there, the lever doesn’t get repelled. So the colors of the image don't just

indicate the force on the lever; you can also interpret them as the voltage at

each spot in the device: black and purple represent high voltage, yellow and green are low.

This is one of my favorite pieces of data that I’ve collected during my research. You and I can’t “see” voltages ordinarily. We rely on “High Voltage” signs to warn us to keep back, and tiny (+) and (-) symbols informing us which way to install a battery. We can't see the electrical pulses traveling up the mouse cable with every click, or the currents running through the wires connecting your earbuds to your phone. But here we have an image that dramatically highlights the “hills” and “valleys” that cause electrons to travel through a circuit.

So the force fields that I use and measure in the lab aren’t exactly the impenetrable shields encountered by the rebels on their assault of the Death Star. Maybe it takes the wind out of the sails a bit, but I still find them pretty cool. For me, these images give textbook physics – voltages, magnetism, force fields – a sense of realness that cannot be captured otherwise. They also keep me humble – no matter how busy I feel my life may be, there are so, so many atoms and electrons buzzing about keeping me alive, holding the “stuff” of everything together, dutifully obeying the laws of physics without complaint. Some people enjoy turning their eyes skyward at night, perhaps peering through a telescope, to put into perspective the happenings of our lives on the grand stage of the universe. I have found an entire other universe down at the microscopic level; one that often goes unnoticed, and is taken for granted. And it is just as marvelous.